COLUMNS

360º Architecture

28 March, 2010

Bokja: ‘A Woman’s Affair’

Bokja, the duo of Lebanese designers Hoda Baroudi and Maria Hibri, are using ancient textiles from the Levant and from countries along the Silk Road to reupholster mass-produced furniture, and transform them into unique works of art.

When one afternoon in 1927 Charlotte Perriand appeared at Le Corbusier’s studio, at 35 rue de Sèvres, and asked for work, he ‘glanced quickly through’ her portfolio of drawings, told her ‘we don’t embroider cushions here’, and threw her out the door. The following day he and Pierre Jeanneret visited her stand at the Salon d’Automne and decided to employ her. As an associate of Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret until 1937, Perriand was responsible for the studio’s furniture and furnishings. The best-known photograph of Perriand is the one that shows her reclining on the chaise longue she co-designed for the Villa Church (Ville d'Avray, 1928–29). By her own account, the man who until recently was habitually credited as the only author of all the iconic furniture the three associates designed together saw for the first time the prototypes of their first tubular-steel-frame furniture at Perriand’s atelier at place Saint Sulpice, and pronounced them ‘delightful’. Perriand got married ‘out of defiance’, and because ‘at the time marriage was the only way for the chrysalis [she] was to turn into butterfly’ and take flight, but refused ‘a frilly white wedding or to look like a fatted calf being led to the slaughter’. Inspired by Josephine Baker, she sported ‘a street urchin’s haircut’ and her ‘ball-bearing necklace’, made of cheap chromed copper balls,(1) and had herself photographed on that special lounge chair of her own creation, the type of furniture traditionally reserved for ‘the man of the house’. The message was lost to design historians who until recently seriously undervalued and marginalized the work of women designers like Charlotte Perriand, Eileen Grey, Margaret and Frances Macdonald, Lilly Reich or Louise Powell.

With notable exceptions such as the metalworker Marianne Brandt, women have been largely excluded from the vast literature on the Bauhaus, even though when the art school opened in 1919 more women applied than men. Walter Gropius’s inaugural address pronouncement, that there would be ‘no distinction between the fair and the strong sex’, betrayed the reality of the school that soon regarded women applicants’ numbers as a problem, applied restrictions and began to confine women students to the weaving workshop, where they could acquire a skill suitable to the domestic world they were considered destined for. In 1926, Gropius announced a ‘policy to discourage women from studying architecture.’ And Oskar Schlemmer derided with a quatrain one of the most productive workshops of the Bauhaus, from 1927 headed by Gunta Stölzl, the only woman teaching at the school: ‘Where there is wool / You’ll find a weaving wench / Be it to fill the idle hours at her bench.’(2)

From the beginning, design history consistently ignored or trivialized women’s non-professional creative activities such as embroidery, weaving and dressmaking (but, significantly, not men’s fashion design), usually performed in the makers’ home, deeming their products intended for the use of the family and therefore unworthy of study by a discipline that focused on mass-produced, industrial objects.(3) The products of needlework arts have been relegated to categories of secondary importance such as traditional or folk art, considered intellectually undemanding, a typically female pre-industrial craft, where modern concepts of authorship and artistic genius do not apply – for their designs do not issue from the hand of an individual master – themselves ideological constructs intended to define art and design as occupations that require intellectual effort and are performed in the public, professional sphere, where the male is dominant.

The nineteenth-century architect Gottfried Semper’s identification of ‘the origin of building’ with ‘the beginning of textiles’ has been misread or delegated to the margins of a canonical theoretical tradition eager to distance architecture from the feminine domain of decoration. It is precisely for the persistent association of ornament and textiles with women that it is worth remembering Semper’s counter-hegemonic postulate of decoration as the production of space itself: ‘Even where building solid walls became necessary, the latter were only the inner, invisible structure hidden behind the true and legitimate representatives of the wall, the colorful woven carpets.’ Opposing the division between high and low arts, and basing his theory of architecture on the low, feminine arts of decoration, Semper wrote in his ‘Style: The Textile Art’: ‘Before the separation [of high and low art] our grandmothers were indeed not members of the academy of fine arts or album collectors or an audience for aesthetic lecturers, but they knew what to do when it came to designing embroidery…It remains certain that the origin of building coincides with the beginning of textiles.’ Semper established the ‘Principle of Dressing [Bekleidung] as the “true essence” of architecture’, and argued that social space was originally defined through the use of woven fabrics, later simulated through paint, a continuation of the textile tradition.(4)

But since at the time of Semper the divorce between high art and craft had been consummated, and the new hierarchy of the arts had established a vast chasm between architecture and embroidery or surface ornamentation, segregated along gender lines, there was no way Semper’s dissident account of the origin of architecture would be tolerated. For centuries and in many societies, the creation of the house and its furnishings has been women’s work. The institution of the dowry is still alive in many contemporary societies. Traditionally, much of unmarried women’s work went into the creation of their dowry, and gave them power and control over the marital home. The Modernist ban on decoration was intended to control and restrict women’s power over architecture and social space. In 1925, Le Corbusier argued: ‘It seems justified to affirm: the more cultivated a people becomes, the more decoration disappears. (Surely it was Loos who put it so neatly.)’(5) Restricting if not outright eliminating women’s decoration work was a mark of civilization and progress. Even though Le Corbusier himself designed tapestries, which he regarded as ‘the murals of the modern age’, he remained unambiguous: ‘I admit the mural not to enhance a wall, but on the contrary, as a means to violently destroy the wall, to remove from it all sense of stability, of weight, etc.’(6) In 1938, he employed murals precisely for the purpose of defacing the architecture of Eileen Gray at her own house (E.1027, Roquebrune, Cap Martin, 1926–29), and without her permission.(7) For Adolf Loos, whose views Le Corbusier shared, ornament with its erotic origins was typical of primitive cultures, peasants and women, who ‘have no other means to fulfil their existence’.(8)

Bokja is a Beirut-based designer duo consisting of Hoda Baroudi and Maria Hibri, two women who over the last ten years have been insatiably collecting ancient textiles from the Levant and from countries along the Silk Road, using them to reupholster furniture with a sort of vibrant and richly textured collage that transforms mass-produced objects into unique works of art. When the two met, Hibri was already an experienced antiques dealer, while Baroudi had already been collecting textiles from Uzbekistan to China. Sharing a love and appreciation for the rich traditions behind these Russian chintzes, tribal suzanis, Anatolian velvets or silk-knit Sichuan brocades, often passed from mother to daughter, they dedicated themselves to preserving their stories and using them to weave new ones. They describe the way they work as ‘very spontaneous. We find a vintage piece of furniture that we fall in love with instantly; it’s usually an one-off piece, a coup de cœur. But then it might sit around for another six months before we do anything with it. We might just waltz around it for days before suddenly having a vision or feeling even regarding how to go about decorating it. One time for example we bought a Pierre Paulin piece – the famous Ribbon Chair – and really for six months we didn’t know how to go about it. Then finally, one day we just felt the urge to attack. The Charles and Ray Eames Lounge Chair on the other hand came very quickly to us.’(9) There is in Bokja’s furniture a clear shift of emphasis from form and structure to surface and ornament, which is perhaps even more powerful when they dress Modernist classics, where a total inversion of hierarchies and subversion of Modernist orthodoxies occur. When they reinvent furniture from the Modernist tradition, their design practise directly confronts and opposes the hegemonic Modernist suppression of the female Other and the domains identified with it: ornament, craft and pre-industrial methods of production.

Hoda Baroudi and Maria Hibri, photograph courtesy of Bokja

Bokja: Eames-à-la-Bokja Chair, left; and Camel Sofa, a ‘coup-de-cœur’ piece, right. Photographs courtesy of Bokja

Bokja: Ribbon Chair, left; and Allo-Oui Swivel Chair, a ‘coup-de-cœur’ piece, right. Photographs courtesy of Bokja

Painstakingly sourced fragments of historic wall hangings from Samarkand and cushions from Bergama may be combined on Bokja’s mobile canvases with pieces from their children’s old clothes, a luxuriously decorated Ottoman baroque sleeve may be married with a piece from a 1960s’ designer dress spotted at a flea market, displaying the marks of its earlier incarnation. Woven tapestries may be matched with sumptuous polychrome silks and shimmering taffeta ribbons, lustrous velvet with crisp linen, soft tweed wool with lace-trimmed satin, elementary stitchwork with luscious brocades, exquisite kilims with block-printed fabrics. Colourful floral motifs meet demure checks and stripes, acid polka dots revere antique silk-thread and sea-shell embroidery. The designers admit that they ‘see potential in everything if used tastefully’, and enjoy mixing, say ‘the opulent with the mundane, the strong with the weak’, juxtaposing historic artefacts with utilitarian fabrics, ‘an ancient rich textile with a fragment of a refugee’s bundle’. The combinations are audacious and unexpected, thoughtful and provocative, challenging aesthetic prejudices and preconceived notions of beauty. They say: ‘We see potential in many fabrics and forms that are overlooked. The Pretty Ugly Chair may not be considered “beautiful” by today’s standards, but we like to always question standards of beauty, of composition and of colour scheme. We are mixers and matchers who like to upcycle fabrics, frames and techniques in a sustainable and fascinating way. We are story tellers. Every piece of fabric, colour, thread, frill that goes into our pieces is a little word from a different part of the world that is chosen in an intuitive process.’

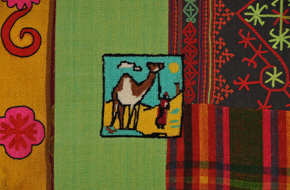

Bokja, details of furniture upholstery, photographs by Styliane Philippou

Baroudi and Hibri strongly reject the categorization of their work as ‘ethnic’, and thus its exoticization and Otherization, which prevents its meaningful appreciation as it perpetuates a Eurocentric – in this case an Orientalist – bias, suggests a peripheral cultural location, and imposes an interpretation by an outsider from an elite centre of cultural production, speaking for the ‘ethnically’ Other, who are not allowed to speak for themselves. Bokja demand, instead, a participation in the system of cultural exchange on the basis of a radical equality of people, genders and cultures. They insist that their creations are utterly contemporary: they mirror today’s world where ‘different cultures interact with one another at an incredible rate’. At times, the form or articulation of a found piece of furniture may guide their process of creation. A particular ornate textile fragment may find a central position on an armchair, and then be slowly surrounded by other pieces, or the form of a piece of furniture may be seen to invite a particular style of fabric. Hibri and Baroudi proceed to dress their found pieces with an eye to ‘the way the form interacts with the materials. Take the Couture Chair for example, which is inspired by the image of a lady dressed in a gown. Initially we were planning on using a set of feminine fabrics to design scarves. But then we happened upon the frame of the Couture, and the fabrics ended up being a perfect match for it. The stout boxy figure of the Couture is complemented very nicely by the lush feminine fabrics, velvets, lace and embroidery that we dress it in. The Couture has become a best-seller’.

Bokja: Couture Chair, a ‘classic’ piece, photograph courtesy of Bokja

Bokja produce two types of furniture: ‘classics’ such as the Couture Chair or the Mickey Mouse Armchair, the frames of which are regularly produced and upholstered uniquely every time, and ‘coups-de-cœur’ such as the Boeing Sofa, the Camel Sofa, the Allo-Oui Swivel Chair and the ingeniously christened Scrambled Egg Chair, a transformation of Arne Jacobsen’s iconic Egg Chair of 1956, whose vintage frames are found, so they are produced as often as these frames become available, usually once or twice. It is worth noting that the designers refer to the furniture they scavenge as the ‘frames’ of their work. To paraphrase Semper, ‘the solid frames are only the inner, invisible structure hidden behind the true and legitimate representatives of the furniture, the colorful fabrics.’

Bokja: Boeing Sofa, a ‘coup-de-cœur’ piece, photograph courtesy of Bokja

Bokja: Schizophrenia Chairs, photograph courtesy of Bokja

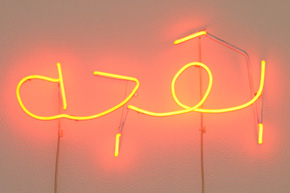

Bokja, the name Baroudi and Hibri have adopted, derives from the Turkish word boğça or bohça, meaning bundle. In Lebanese, bokja describes a bride’s dowry, wrapped in an intricately embroidered textile. ‘It is custom in this part of the world for a young woman to carry a dowry with her when she gets married,’ they explain. ‘Both of us had bokjas when we got married that carried linens and hand-embroidered towels. We look back fondly on that moment in our lives.’ One of the first foot stools they made was covered with the type of fine Ottoman wrapping used in these bokjas or dowry bundles. ‘Later on, through our work, we discovered that the term “bokja” is actually used in many countries in the region, from Turkey to Syria to Uzbekistan.’ The word μποχτσάς has the same meaning in Greek and is of the same origin. Bokja’s furniture – chairs, armchairs, sofas, ottomans, day beds etc. – preserves both the textiles that were lovingly produced by young women and their female relatives to furnish, enrich and embellish their homes, and the stories of these creative women. Each one of their unique pieces comes with a ‘passport’ that lists the textiles and their provenance, and describes the weaving and embroidery traditions to which their constituent parts belong. But these stunning pieces do not merely preserve the heirloom treasures of innumerable women who laboured patiently over their looms and needlecraft; they also revalorize and radicalize the products of the creative activity of generations of women – weavers, embroiderers or dressmakers – which had been trivialized and expelled from the male-dominated world of art and design, using them as a tool to abolish established hierarchies of art and craft, and subvert hegemonic discourses.

Bokja: Mickey Mouse Chair, a ‘classic’ piece, photograph courtesy of Bokja

By their adoption of ornamental textiles as the material with which they work, gender has become central to Bokja’s design work. ‘It’s really a woman’s affair,’ they assert. Their creations have been compared with the work of the Campana brothers. But rather than capitalizing on the exotic appeal of ‘primitive’ craft, like Fernando and Humbero Campana do, romanticizing and commercializing the marginal and the feminine, Hoda Baroudi and Maria Hibri mix the mass-produced with the homespun, the industrial with the traditional, the product of what has been viewed as the public, male world of work and capitalist production with the product of what has been viewed as the private, female world of home and family (procreation). They mobilize, emancipate and empower the work of the forgotten female homemakers of the past, transforming it into a powerful instrument of invention and liberation, a medium with which to produce contemporary design work that brings the anonymous into the authored, launches the peripheral into the centre, re-incorporates the domestic domain of the feminine into the public space of artistic and capitalist production. In Bokja’s work, dressing or wrapping is not a secondary craft; textiles are the production of furniture itself, and of a new kind of social space. They create contemporary bokjas, lavish bundles, which no longer confine their treasures to women’s homes; and they pass them on to the next generation of women and men as a precious, patiently and thoughtfully created dowry.

Bokja furniture, photographs by Styliane Philippou

Hibri and Baroudi express a clear concern for local women’s exclusion from the cycles of production, including cultural production, and proudly stress that they ‘are two women who design the furniture at Bokja from A to Z and who also run the company completely. We believe in the capabilities of women to contribute in the work force, and not just to contribute but also to lead their own initiatives, and to be their own bosses. Women have potential that is often overlooked by society or not capitalized on. Through our work we hope to show that women are a valuable resource that should be invested in and that can invest in themselves and help build their societies.’ They have made it ‘part of Bokja’s mission to help out and empower women who have fallen on hard times.’ They regularly incorporate in their products the aubusson needlepoint work of local female prisoners. Their ‘atelier has a beautiful energy with three women (widows) – Jihad, Rahmeh and Jamal – whom [they] employ for their intricate embroidery.’ Hibri and Baroudi explain: ‘In this part of the world, men are the traditional bread-winners in the family, so by employing widows we offer them a means of supporting themselves and their families and we instil them with hope.’ Through their design work and methods of production, they problematize questions of gender with regard to the social and the professional subordination of women as well as with regard to the production of cultural artefacts. They challenge sex-role stereotypes, and traditionally segregated cultural roles and divisions of labour. And they synthesize skills and roles traditionally viewed as masculine or feminine.

Bokja, details of furniture upholstery, showing aubusson needlepoint work by local female prisoners.

Photographs by Styliane Philippou

Rahmeh, one of the ladies producing embroidery work at Bokja’s atelier, photograph courtesy of Bokja

All the Bokja pieces are exquisitely crafted, with great attention lavished on every detail. ‘Starting our business from scratch with the mission to use authentic and traditional techniques and embroidery we have built a network of strong relations with the best local artisans, carpenters and upholsterers. This network has grown over the past ten years. The artisans we work with still use traditional techniques that have been passed on over the generations and that make their work stand out. We go to their different neighbourhood ateliers to get everything done by hand. They are now all part of the Bokja family.’ The word that inspired bokja – بغچۀ – may also be vocalized as باغچۀ that is bağçe or bahçe, a word of Persian origin meaning garden.(10) Every piece of Bokja’s furniture is truly a lovingly cared for garden, infused with its creators’ fascination for ‘the richness of the colours of the natural dyes used in these old fabrics and textiles, and the sensuality and diversity of the textures. We like to create landscapes of colour in our furniture, we like to use bold colours and to be generous with details.’

Local artisans who collaborate with Bokja, photographs courtesy of Bokja

Bokja, furniture details, photographs by Styliane Philippou

Hoda Baroudi and Maria Hibri have recently also started designing their own frames in varnished mild steel, upholstering them with the exuberant colours and patterns they tirelessly continue to source from women artists and artisans across the region. They are particularly fond of bird motifs, ‘very popular in traditional Ottoman and Uzbek fabrics’. Their recently designed mild-steel coffee tables feature intricately-cut, lace-like patterns, a novel interpretation of traditional embroidery motifs where birds are frequently encountered. ‘Anything with birds appeals to us,’ they say. ‘We started to incorporate birds into our designs, and then we decided that whenever we would have two birds in our designs they would represent us, two energetic designers. Sometimes we explore roosters in our designs as well.’ Baroudi and Hibri enjoy their work enormously. Integrating work and play, they are hugely productive while they also have lots of fun. At times they may dress a children’s toy or anything else just for the fun of doing it. Their imaginative design work is both their means of livelihood and a source of pure, unproductive pleasure. Bokja’s aesthetics springs directly from a radical re-evaluation of the often disregarded space of the beautiful, the ornamental, the ludic and the pleasurable.

Among Bokja’s latest creations: bench with mild-steel frame, photographs by Styliane Philippou

Among Bokja’s latest creations: mild-steel coffee tables with intricate, lace-like patterns and bird motifs, photographs by Styliane Philippou

Bokja: the firm’s logo on the wall of their Beirut shop, left; and a children’s toy car upholstered by Bokja

and used as a business-card holder, right. Photographs by Styliane Philippou

Notes

1 Perriand, Charlotte, 2003, A Life of Creation: An Autobiography (New York: Monacelli Press), pp. 20–31.

2 See Baumhoff, Anja, 2006, ‘What’s in the Shadow of a Bauhaus Block? Gender Issues in Classical Modernity’. In Practicing Modernity: Female Creativity in the Weimar Republic, ed. Christiane Schönfeld (Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann), pp. 51–67.

3 See Buckley, Cheryl, 1989, ‘Made in Patriarchy: Toward a Feminist Analysis of Women and Design’. In Design Discourse: History, Theory, Criticism, ed. Victor Margolin (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press), pp. 251–63.

4 Quoted in Wigley, Mark, 1992, ‘Untitled: The Housing of Gender’. In Sexuality & Space, ed. Beatriz Colomina. Princeton Papers on Architecture Series (New York: Princeton Architectural Press), pp. 367–70.

5 Le Corbusier, 1987, The Decorative Art of Today (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press [1925 in French]), pp. 85–87, emphasis in the original.

6 Letter from Le Corbusier to Vladimir Nekrassov, 1932, quoted in Colomina, Beatriz, 1996, ‘Battle Lines: E.1027’. In The Sex of Architecture, ed. Diana Agrest, Patricia Conway and Leslie Kanes Weisman (New York: Harry N. Abrams), p. 174.

7 See Colomina, pp. 174. ‘Later on, Le Corbusier actually got credit for the design of the house and even for some of the furniture.’

8 Loos, Adolf, 1962, ‘Ornament und Verbrechen’ (1908). In Adolf Loos, Sämtliche Schriften (Vienna: Herold), p. 287. See also Tournikiotis, Panayotis, 2002, Adolf Loos (New York: Princeton Architectural Press), pp. 23–27. Tournikiotis argues that, despite widespread interpretations following the French publication of Loos’s famous manifesto ‘Ornament and Crime’ (first published in Les Cahiers d’Aujourd’hui in June 1913 and reprinted in the first issue of L’Esprit Nouveau on 15 November 1920), Loos ‘did not insist on the suppression of all architectural ornament: it is clear that he does not compare “the superfluous” ornamentation of the Secession (and generally of Art Nouveau) with the “grammar” of classical ornament – of which, on the contrary, he approved and which he practiced’. According to Tournikiotis, ‘Loos gave women the right to ornament, for erotic significance’; Tournikiotis, pp. 23, 26.

9 This and the following quotations are from Bokja’s website http://www.bokjadesign.com, from my discussion with Maria Hibri in Beirut last January, and from my subsequent correspondence with Hoda Baroudi and Maria Hibri.

10 I am grateful to the Turkologist Natasha Lemos who pointed out this connection to me.

Related articles:

- 360 Degrees Architecture ( 10 October, 2009 )

- Τhe Roots of the Industry of the Image ( 27 October, 2009 )

- Anish Kapoor: Non-objective Objects ( 26 November, 2009 )

- Love Thy Planet ( 28 December, 2009 )

- Europe’s Civilization under Threat ( 28 January, 2010 )

- Made of Stone and Water, for the Human Body ( 28 February, 2010 )

- Brasília from the Beginning, Fifty Years Ago ( 07 April, 2010 )

- Brasília, ‘capital of the highways and skyways’ ( 30 April, 2010 )

- Oscar Niemeyer’s Permanent International Fair in Tripoli ( 29 May, 2010 )

- Learning from Miami ( 10 July, 2010 )

- The Greatest Show on the Beach ( 08 August, 2010 )

- Oscar Niemeyer: Curves of Irreverence ( 28 March, 2011 )

- The Lizards of Djenné ( 26 September, 2010 )

- Transformed by Couture ( 29 October, 2010 )

- Another Athens Is Possible ( 02 December, 2010 )

- From Juan O’Gorman for Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo ( 28 February, 2011 )

- Roberto Burle Marx: The Marvellous Art of Landscape Design ( 27 May, 2011 )

- The Danger that Lurks on this Side of the Gates ( 10 September, 2011 )

- Eduardo Souto de Moura ( 21 November, 2011 )