ARCHITECTURAL REVIEW

18 August, 2010

REFUGE IN ARCHITECTURE

The Education Legacy of Frank Lloyd Wright. By Aris Georges, M.Arch, Professor of Architecture, Taliesin.

The school of architecture founded by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1932 has long espoused principles of ecological sensitivity and alternative education. While for decades this aspect of the school has rarely been studied in the numerous historical works and publications about Wright, it is now beginning to attract a wider interest. This is partly because amid a momentous green consumerism people seek to understand issues of sustainability as they relate to the built environment, and partly due to the recent exhibition about Wright at the Guggenheim Museum-particularly the Learning by Doing exhibition that examines the school's shelter design/build program. It is quite possible that the general public knows little of Wright as a pedagogue and usually considers his architecture a personal, if not idiosyncratic, matter.

Despite the fact that the exhibit of the shelters casts light on one of the significant activities of students, it does not set it in the context of the evolution of the school itself, something that ultimately brings to the surface more questions than it answers about the educational philosophy of Taliesin. Before expanding on the shelters as lessons of tangible architecture (or nevertheless technique), it is important to seek the notion of refuge in Wright's tempestuous course after Chicago, which has left its mark on the school.

In 1909, Wright self-exiled in the outskirts of Florence, fleeing a flourished career in the suburb of Oak Park, with the spouse of his client Edwin Cheney. He writes in his autobiography, "In ancient Fiesole, far above the romantic city of cities, Firenze, in a little cream-white villa on Via Verdi, the rebel. How many souls seeking release from real or fancied domestic woes have sheltered on the slopes below Fiesole! I, too, now sought shelter there in companionship with her who, by force of rebellion as by way of love, was then implicated with me."

Upon his return, Wright discovered that his scandalous flight proved inexcusable and his career was considered finished. A drawing dated March,1911, depicts a small cottage for Wright's mother on the slopes of a hill belonging to her Welsh immigrant family alongside the Wisconsin River. Three months later, in June 1911, the cottage plan becomes the expanded design of Taliesin I, and Wright immediately began its construction, taking his second refuge in the green landscape of un-glaciated and utterly pastoral southwest Wisconsin.

After surviving two tragedies that destroyed the residence, with its subsequent reconstruction Wright manages to convert his refuge into a fortress and springboard, from which, for the remainder of his life, he will leave us some of the most important designs and texts of architecture. Taliesin is not place of withdrawal but a platform to campaign outwards. It is here where Wright will mount his battle with the modern movement; a fight he will tirelessly pursue until his death.

However, Wright's battle with the modern movement is often ironic. Even though he has been a staunch proponent of an organic, indigenous American architecture, his focus remains on his work and his clients. Though polemic in a very public protest against the modernists, he doesn't make a systematic effort to build a theory of organic architecture, resorting to the loftier philosophical treatises that he so admired in his American Transcendentalist mentors. The Taliesin productivity of the past three decades of Wright's life is striking, with commissions of about 30 projects per year. It is true that the school and committed students participated in this productivity, imbuing the work with youthful creative energy.

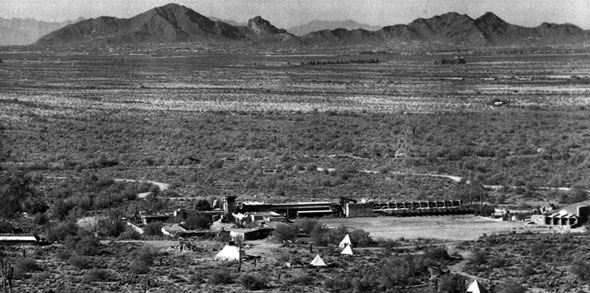

Armed with his spirit of free adventure-by then quite a survivor-in the mid 1920s, a few years before the creation of the school, Wright fell in love with the Arizona sunshine through commissions by Alexander Chandler, for whom he designs three major projects. Chandler provided land for a camp in the Sonoran desert that Wright dubbed Ocotillo, where he first experimented with ephemeral lightweight construction. The camp will be the precursor to Taliesin West.

In Ocotillo ceilings were made of canvas stretched over wooden frames, and its foundations were based on poles that could be removed without leaving traces in the rocky ground.

Within a decade, the school was established and in 1937 construction of Taliesin West, exclusively with the personal work, effort and sweat of students, commenced. Thus begins the tale of the two Taliesins, between which the school will move twice a year, avoiding the harsh Wisconsin winters and the scorching Arizona summers respectively. This trip continues to this day, giving students the opportunity to cross the vast landscapes of the great plains at a distance almost 2,000 miles every spring and autumn.

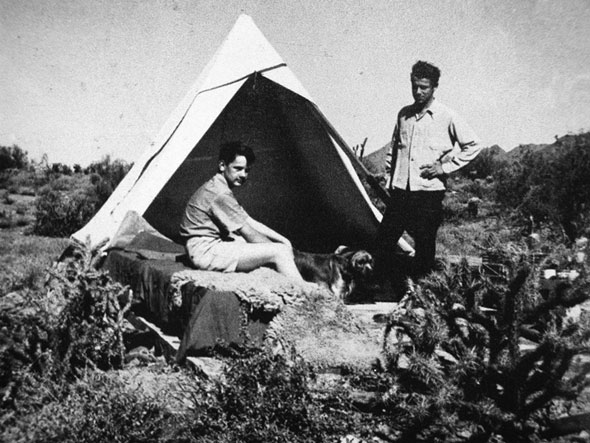

The first desert shelters were canvas tents over wooden bases. Inside, a bed with a sleeping bag, candles or gas lamps, books, and a flashlight. Other possessions were stored in a small building that had locker rooms and bathrooms.

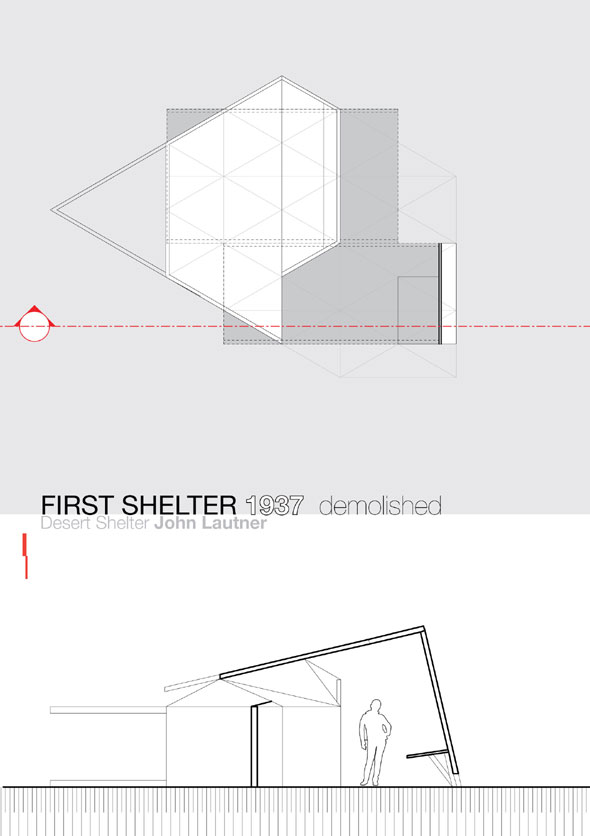

One of the first students who internalized the poetry of habitation in the crisp desert landscape and studied the shelter as architectural miniature was John Lautner, who later became well known in Los Angeles. Lautner sought elementary tectonics that he based on the grammar of Taliesin West, with the iconic rotation of the Right Angle at 15°.

To a sleeping area he adds an open canopy where he places his drafting table with views of the McDowell Mountains and the horizon of the Valley of the Sun. This translation of the simple tent to a miniature-architecture will emerge later as the proving ground for students who are concerned with their own architectural voice. As it is natural, in the decades following we find a distinction between the students who designed under the influence of the Master, and those who broke away from the architectural vocabulary of Wright to develop their own, personal phraseology. For them the shelter was not only a study in architectural scale, but also a refuge that neutralized the influence of the doctrine. Interestingly enough, it is Wright himself who prompted his apprentices to not mimic him but to seek their own architecture in the source of "Nature" that he so loved.

Consequently, the shelters hold a strong historic role in the development of architecture at Taliesin, particularly post-Wright, and even today the old structures pose relevant questions to students. The difference is that today the students do not have to avoid Wright necessarily, but what they perceive as 'fashion" and "trend" in contemporary western models of architecture. Therefore, the experience of wrestling with ideas and maturing through ideology, amid a proliferation of information, prompts students to seek architectural values and take a position toward them.

Two years ago, on the initiative of graduate students, a new effort was launched for the construction of shelters at the Taliesin campus in Wisconsin. The shelters were dubbed prairie shelters, to differentiate them from the desert shelters. In order to achieve this initiative, students undertook the preparation of documentation with which they requested from local authorities variances to local building regulations to allow experimental structures. The procedure gave students the experience of transaction with regulatory bodies to consider experimental construction as a new building category.

As a start, two shelters were built exploring the new environmental challenges of the northern climate, paving the way for the continuity of a tradition that was limited to the challenges of the desert. The environmental conditions in Wisconsin are almost contrary to the southwest desert climate. Here the soil is sedimentary and freezes deep. The foundation becomes a critical element in the design and requires more material. Rain and snow, abundant most of the time, require particular attention to waterproofing and live structural loads. Compared with the almost inert desert, the environment in Taliesin is alive and demanding. Consequently the distinct lessons between the two campuses cover a wide range of problem solving and implementation of ideas.

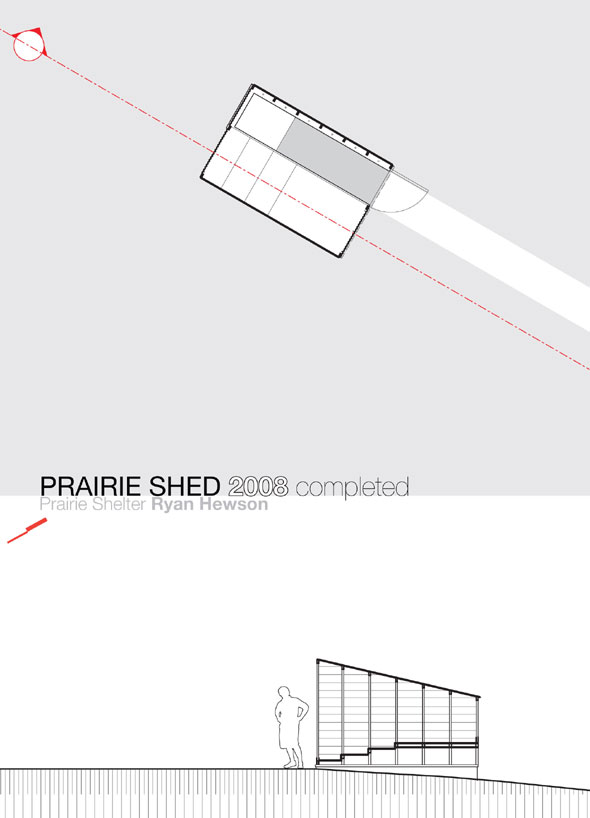

The two prairie shelters under construction are seeking two different architectural adventures. The Prairie Shed by Ryan Hewson is carried out with the 80% of the materials harvested by demolition and recycling of a 1930’s structure, situated at a nearby farm. The design is an architectural study in the morphology of vernacular sheds scattered on the farms of Wisconsin. Ryan studied the cantilever, structural frame, bending moment, and sheer wall.

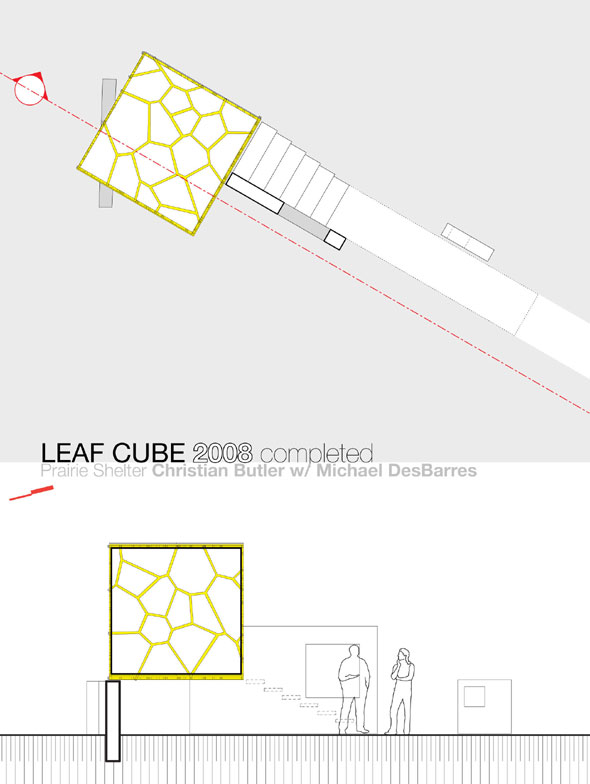

In the Leaf Cube—a collaboration between Michael desBarres and Christian Butler—the focus was on digital computations of the Voronoi algorithm as a basis to develop six non-uniform patterns that formed a steel cube anchored on a reinforced concrete base. While there are no two identical polygons in the design, the digital computational power was used in order to minimize the waste of material, and to optimize the position of each segment in the lengths of the steel tube before cutting.

This brings to focus a current issue in architectural theory, namely the apposition between advances in digital computation that promote an iconic conception of architecture, and the increasing need for strategic management of building material resources in line with the ecological concerns. Perhaps the gap appears unbridgeable at present, but when new generations of architects have the opportunity of direct experience with these issues, supported by an educational philosophy of experimentation, it is quite probable that they find the balance between the virtual reality of electronic design tools and the physical reality of materials which are more and more sought in recycling and sustainable practices.

Even though Wright had strong affinity for the Transcendentalists, elements of the educational philosophy at Taliesin may be traced to William James’ theory of radical empiricism. James, together with Peirce at Harvard, was a pioneer of pragmatism, and he developed the well-known theories of free will and a pluralistic universe. In the mid nineteenth century James concluded that the experience of reality is through direct contact with the correlations of multiple experiences that synthesize a holistic network of memory and stabilize knowledge. This theory, which probably heralded the development of quantum physics, found fertile ground in the purely empirical approach to education at Taliesin. In recent years the evolution of Taliesin’s pedagogy finds sympathetic resonance with the theories of self-determination (competence, autonomy, relatedness) and of reflective practice (stochastic development). Such an educational background offers students a completely alternative course within higher education in architecture that prepares them for the complex professional dynamic on one hand, and for a relentless lifelong learning on the other.

Within this context, the shelter is not limited to being the symbolic icon of an architect’s identity but becomes a laboratory of ideas whose aim is not so much creative expression, but the exploration of architectural goals and objectives. Even in cases of error and failure, the student architect learns to live with them, which ultimately brings awareness to the impact of design decisions on life itself.

The multi-faceted notion of refuge asserted by Wright, and consequently by students at Taliesin, remains rich in substance and experimental. Although few of the fifteen hundred architects who passed through Taliesin achieved wide recognition for their own work (Fay Jones, John Lautner, Paolo Soleri, Richard Neutra, Rudolph Schindler), one must not overlook the fact that the creativity and the commitment that this stream of talent gave to the school is a critical part of its seventy-five year history. Moreover, Wright affectionately called Taliesin a “little experiment” and urged students to find inspiration in his sources and not in him. Tradition, when it follows principles rather than form, survives even in difficult and adverse circumstances. This tradition of empirical education of architects at Taliesin is kept alive and remains relevant to the wider issues of architectural education.

Both exhibitions will open this Fall at the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, where the two Franks, Wright and Ghery, will once again fuel our impetus to continue the discourse on the substance of architecture.

Aris Georges, M.Arch, Professor of Architecture, Taliesin.

Related articles:

- Contemplating the Void—Create Your Own Guggenheim Intervention. ( 20 June, 2010 )

- Working with Frank Lloyd Wright ( 03 July, 2011 )