COLUMNS

360º Architecture

28 February, 2010

Made of Stone and Water, for the Human Body

Peter Zumthor’s Thermal Baths in Vals, Switzerland (1990–96)

The real has its own magic.

Peter Zumthor

The first writing exercise I used to give to my first-year architecture students at the University of Plymouth was to ask them to review Peter Zumthor's collection of essays, published under the title Thinking Architecture.(1) Students found the texts inspiring and useful as an introduction to Zumthor's built work. These texts also helped dispel the idea or, rather, the fear that reading or writing about architecture is 'difficult'. Zumthor's direct, clear, concise and pleasurable prose has nothing of all that obscure, pretentious and irritating architectural rhetoric, which seeks to justify unimaginative, arbitrary formal choices with infantile metaphors, naive interpretations of history and tradition, or grandiloquent statements devoid of substance. Not for Zumthor the passionate intensity of self-gratifying ideology or poorly-digested philosophy, nor the empty 'sustainability' claims.

Peter Zumthor's buildings share the same qualities of clarity, coherence, precision and exactitude. They are straightforward, radically simple and severe, with no superfluous parts, and nothing 'too leisurely and nice', as he would say. They have a strong material presence, powerful and moving, seductive even. Few days ago I visited his extraordinary thermal baths in Vals for the third time in ten years. It is one of those buildings that make me want to return again and again. And it is also one of those buildings that cannot be fully appreciated by 'the least sensual of the sensations, the visual'.(2) It has been masterfully interpreted by great photographers, like Hélène Binet, yet it can only be experienced as architecture by the human body; in this case, by the bather's body that moves slowly through its cavernous sequence of spaces, discovers it step by step, immersion by immersion, meanders between its mighty stone pillars, sweats on warm black basalt stones, seeks the shadows or follows cracks of water and light, is soothed in therapeutic and purifying waters, reinvigorated under gushing fountains, enveloped in rising steam, pulled by the daylight and views, seduced to lie and rest. Things like texture, temperature and humidity, resonance and smell play an extremely important role in a building that awakens, and demands to be experienced by, all the senses. This was precisely the architect's intention: 'to create a sensuous environment for the human body, for naked skin, for young bodies and old bodies, which look beautiful in the soft light or half shadows...We wanted to create a place of rest and relaxation for the encounter between the human body and the water issuing from the spring in the mountainside just a few meters above the baths: vigorous, self-contained and rooted in the valley'.(3)

Peter Zumthor, Thermal Baths, Vals, 1990-96, photographs by Styliane Philippou

There are two sorts of imagination, argued Gaston Bachelard: 'a formal imagination and a material imagination'. Images of matter, he wrote, 'stem directly from matter. The eye assigns them names, but only the hand truly knows them'.(4) Zumthor's imagination stems directly from the 'things themselves', from 'real things', 'concrete things' and 'factual relationships'. He insists on 'the reality of building materials',(5) but, for him, water, shadow and light are building materials as concrete as stone and steel. He speaks, for example, of having gone about 'plan[ning] the building at Vals as a pure mass of shadow, then...add[ing] light as if it were a new mass seeping in.'(6) Like in the old hammams, Zumthor says that the design work 'focused largely on the interior. The exterior of the building, the large stone block protruding from the mountainside, evolved and acquired its form from inside out'. To reinforce its introvert nature, although an independent structure, the bath building has no entrance from the outside. It is accessed via a long, narrow and dark subterranean passage from the main building of the neighbouring 1960s' hotel complex. Yet, the access to the internal 'landscape of basins and blocks' does not lack ceremony. The passage leads to the long 'fountain hall', where the raison d'être of the baths is revealed: water from the spring spouts from five brass pipes at head height, leaving painterly traces of ochre and rust on the concrete walls and stone floor. Beyond the antechamber of the changing rooms, a raised stone platform offers the first views towards the spatial continuum of the bathing landscape. A long stone staircase descends to the bathing level.

Peter Zumthor, Thermal Baths, Vals, 1990-96, photographs by Styliane Philippou

The design emphasis on the interior of the building may also be the reason I have come to enjoy it more during the winter time, when the snow-covered terraces and mountain on the opposite side of the valley, and the vapour-filled air in the outdoor pool bring into the building water in all its states. The all-important, 'factual' relationship between the two main building materials of the thermal baths, water and stone, is also heightened during the cold season, when all parts of the monolith are in contact with water: liquid, solid or gaseous. Having no marked point of entry, the bath building conveys more forcefully the architect's idea of a homogeneous structure rooted in the mountain, 'a large porous stone' built of stone: 'the section and profile of the structure as a whole is determined by a continuous series of natural stone strata - layer upon layer of Vals gneiss, quarried 1,000 meters/3250 feet further up the valley, transported to site, and built back into the same slope'.(7) Creating a building that responds to the topography and the geology of the site - 'the stone masses of the Vals Valley, pressed, faulted, folded and sometimes broken into thousands of plates' - did not mean designing something that looks like it is not made by human hand. On the contrary, what grows out of the slope is a technically ordered, skilfully constructed architectural work. Rectilinear geometry is rigorously pursued, and its visibility guarded even in winter, when heated glass strips between the fifteen rectangular, snow-covered roof slabs ensure that the right-angled roof mosaic is not obscured. Nothing is allowed to 'compete with the human body...Only the anatomically undulating wooden deck chairs, designed especially for the baths, hint at the softness of the human body'.

Peter Zumthor, Thermal Baths, Vals, 1990-96, photographs by Styliane Philippou

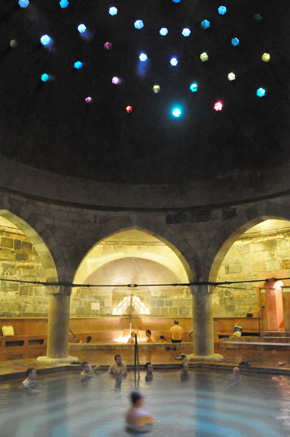

Even before the decision to construct the building entirely of stone - 'stone, that is to say sand, gravel and cement mixed to make concrete, and gneiss from Vals' - there was the idea of 'inventing a building that could somehow always have been there...older than anything already built around it'. The local topography and geology suggested that this may be achieved by 'hollowing out a huge monolith'. And the idea of chiselling out 'boulders standing in the water' was inspired by an old advertising campaign for the local bottling company, showing 'a primordial landscape of water with towering, jagged mountains' rising from the sparkling waters of Vals. Architectural ingredients for the project were found in the weatherproof stone roofs all over the valley - 'their structure reminiscent of reflexes on water' - the walls and rock formations, the stone quarries and the mighty civil-engineering works strewn on the surrounding mountains - tunnels, galleries, dams - and in a colour photograph of Budapest's Ottoman Rudas Baths - 'the starry sky of the cupola illuminat[ing] a room that could not be more perfect for bathing: water in stone basins, rising steam, luminous rays of light in semidarkness, a quiet relaxed atmosphere, rooms that fade into the shadows...something serene, primeval, meditative...utterly enthralling'.(8)

Left:Peter Zumthor, Thermal Baths, Vals, 1990-96, central indoor pool, photograph by Styliane Philippou

Right:Ottoman Rudas Baths, Budapest, 1550, central indoor pool, photograph by Styliane Philippou

The long process of research in spatial composition, through endless 'quarry sketches', later called 'block studies', was concerned with 'mass and hollow, openness and compactness, rhythm, repetition and variation'. It involved 'cutting gigantic tables out of the blocks [of an imaginary] quarry, then joining them together and stacking them on top of each other', and eventually produced the image of 'one single mass of stone, hollowed out from the front, from the top, from inside. What emerged were...mighty "tables of stone," great stone columns with cantilevered tops'. A score by John Cage was found inspiring at the initial stage of rhythmic plan notation, while Piet Mondrian's painterly compositions were considered for the ordering of the blocks and the 'meander' around them. The stone pillars were hollowed out in turn to house various intimate, cavernous 'introverted rooms': the dark-red-wood panelled vestibules; the red-walled 'fire bath' (42°); the blue-walled 'ice bath', a one-person immersion pool (14°); the black-walled, lavender-fragrant 'flower bath', where marigold petals shimmer in the underwater light; the 'drinking stone'; the tough-sawn-stone-walled, six-metre-high 'sound bath' or 'resonance room'; the dark, leather-upholstered 'sounding stone', a dark chamber for which Fritz Hauser composed the sound installation Wanderungen (Wanderings, 1996), entirely produced by oscillating stones; the 'sweat stone', two parallel sequences of dimly lit steam rooms; the massage room; the shower and toilets; and the quiet resting area with a view to the other side of the valley. Four of these rectangular stone columns demarcate the central indoor pool, arranged in a pinwheel fashion, granting bathers a space protected from the surrounding circulation zone. Between the stone blocks, steps descend into the water of the central indoor pool, which reaches up to the floor level, allowed to flow over the top step into one of the overflow seams.

Peter Zumthor, Thermal Baths, Vals, 1990-96, photographs by Styliane Philippou

Bachelard observes that 'formal imagination needs the idea of composition. Material imagination needs the idea of combination.'(9) At the thermal baths in Vals, Zumthor paid minute attention to the various combinations of stone and water ('and a speck of gold...bits of jewelry on stony ground: bronze, brass, little bits of black steel and sparkling chrome') to produce sensual effects.(10) The uniformity of water is matched by a generally uniform treatment of the stone containers. The refinement of the stone surface heightens the quality of depth, the value that belongs singularly to water. And water tames what Nietzsche called 'the harsh divinity of the savage rock'.(11)The stratified surface of the walls helps to transmit the richness and density of matter and the material experience. It was produced through stacking of thin bands of Vals gneiss, in three different thicknesses (31, 47 and 63 mm), two depths and different lengths, in various sequences, according to a precisely specified pattern. The stones were firmly bonded together with 'liquid stone' or concrete, poured at the back of the stone wall or between two walls of layered stone, a technique that was inspired by 'older retaining walls on mountain roads', and became known as 'Vals compound masonry'.(12) The courses of stone were layered flush one on top of the other on the exposed side of the wall, and staggered on the back, to enhance the concrete bonding. Slabs of the same stone were also used on the floor of the indoor and outdoor pools and circulation areas as well as on certain ceilings, on stairs, door openings and benches. The remarkable simplicity of the building's appearance is the result of sophisticated structural engineering, and painstaking, complex detailing that achieved the desired integration of waterproofing, thermal insulation, expansion joints and services in the structural mass of the building. 'The building looks simple,' asserts Zumthor, 'the complexity is hidden in the mass'. Every element of the thermal baths building, from the stone courses to the lintels and steps is carefully calibrated to achieve a continuous 'fabric whose texture flows in an even, uninterrupted rhythm'.

Peter Zumthor, Thermal Baths, Vals, 1990-96, photographs by Styliane Philippou

'Studying the art of bathing influenced our architecture,' says Zumthor. Together with the citizens of Vals, who supported the uncompromising architect even when the team of marketing and development specialists quitted the project in protest over the unconventional, and in their view elitist design of the baths, Peter Zumthor explored the rituals of cleansing and bathing and invented an original sequence of spaces for multiple, pleasurable bathing experiences. Bathers delight in discovering the various sensations of immersion in waters of different temperatures, in pools of various spatial and lighting conditions, surrounded by different colours, materials, sounds, aromas and textures, gushing or gurgling waters.

The large cube 'that looks as if it had grown out of the mountain' was opened to the sky and the panoramas towards the mountain slope dotted with small barns, and the village down the valley. Large and small openings reflect the scale and proportions of those found in the old structures of the Vals valley, stone barns to store hey and timber village farmhouses, all with roofs of Vals gneiss. Daylight filters through the long cracks between the stone table tops, and water flows in some of the joints of the floor slabs, set on a different pattern, producing an effect reminiscent of the lines of grass that grows between the stones. At different times of the day, the light that penetrates through the 6 cm-thin seams between the ceiling slabs washes the walls of certain pillar blocks aligned flush with one side of their ceiling slab. Drains, overflows and the building's expansion joints are integrated in the linear pattern of the rectilinear floor mosaic. Atop the roof mosaic of the prestressed concrete slabs was laid a 'soft carpet of the rough, wild flower meadows of the valley slope'. Four rows of four square skylights of blue glass, inspired by the round, multi-coloured openings in the domes of Turkish baths, are reserved for the central slab, suspended as if by magic above the large indoor pool. A set of external bluebell-like lamps ensures the effect is preserved in the nights when the baths impose on the bathers a regime of silence for a different, more profound experience of stone and water. At daytime, the steaming outdoor pool is animated by the roaring water gushing violently from three brass pipes - these are also silenced for night bathing.

Peter Zumthor, Thermal Baths, Vals, 1990-96, photographs by Styliane Philippou

Notes

1 Zumthor, Peter, 1998a, Thinking Architecture (Baden: Lars Müller).

2 Bachelard, Gaston, 1983, Water and Dreams: An Essay on The Imagination of Matter, trans. Edith R. Farrell (Dallas: Pegasus Foundation [1942 in French]), p. 20.

3 Unless otherwise indicated, all quotations are from Zumthor, Peter, 2007. In Peter Zumthor Therme Vals (Zurich: Scheidegger & Spiess), pp. 23-27, 38-47, 62-70 and 80-91.

4 Bachelard, p. 1, emphasis in the original.

5 See Zumthor, 1998a.

6 Quoted in Hauser, Sigrid, 2007. In Peter Zumthor Therme Vals, p. 75.

7 Zumthor, 1998b, Buildings and Projects 1979-1997 (Baden: Lars Müller), pp. 156-57.

8 Zumthor, 2007, pp. 24-27.

9 Bachelard, p. 93.

10 'And this is what I would call the first and the greatest secret of architecture, that it collects different things, different materials, and combines them to create a space.' Zumthor, Peter, 2006, Atmospheres: Architectural Environments, Surrounding Objects (Basel: Birkhäuser), p. 23.

11 Quoted in Bachelard, p. 161.

12 Quoted in Hauser, p. 169.

Related articles:

- 360 Degrees Architecture ( 10 October, 2009 )

- Τhe Roots of the Industry of the Image ( 27 October, 2009 )

- Anish Kapoor: Non-objective Objects ( 26 November, 2009 )

- Love Thy Planet ( 28 December, 2009 )

- Europe’s Civilization under Threat ( 28 January, 2010 )

- Made of Stone and Water, for the Human Body ( 28 February, 2010 )

- 2008 ( 01 January, 2010 )

- Bokja: ‘A Woman’s Affair’ ( 28 March, 2010 )

- Brasília from the Beginning, Fifty Years Ago ( 07 April, 2010 )

- Brasília, ‘capital of the highways and skyways’ ( 30 April, 2010 )

- Oscar Niemeyer’s Permanent International Fair in Tripoli ( 29 May, 2010 )

- Learning from Miami ( 10 July, 2010 )

- The Greatest Show on the Beach ( 08 August, 2010 )

- Oscar Niemeyer: Curves of Irreverence ( 28 March, 2011 )

- The Lizards of Djenné ( 26 September, 2010 )

- Transformed by Couture ( 29 October, 2010 )

- Another Athens Is Possible ( 02 December, 2010 )

- From Juan O’Gorman for Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo ( 28 February, 2011 )

- Roberto Burle Marx: The Marvellous Art of Landscape Design ( 27 May, 2011 )

- The Danger that Lurks on this Side of the Gates ( 10 September, 2011 )

- Eduardo Souto de Moura ( 21 November, 2011 )

- RIBA Royal Gold Medal 2013 ( 02 October, 2012 )

- Steilneset Memorial by Peter Zumthor and Louise Bourgeois, Norway ( 18 December, 2012 )

- Peter Zumthor Lecture - Royal Gold Medal 2013 ( 31 March, 2013 )